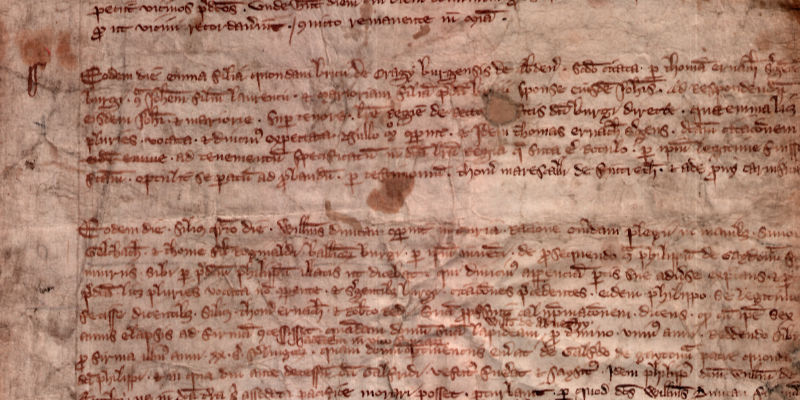

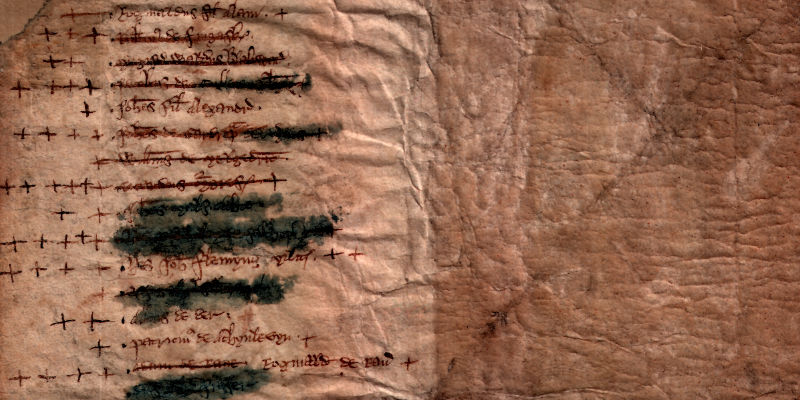

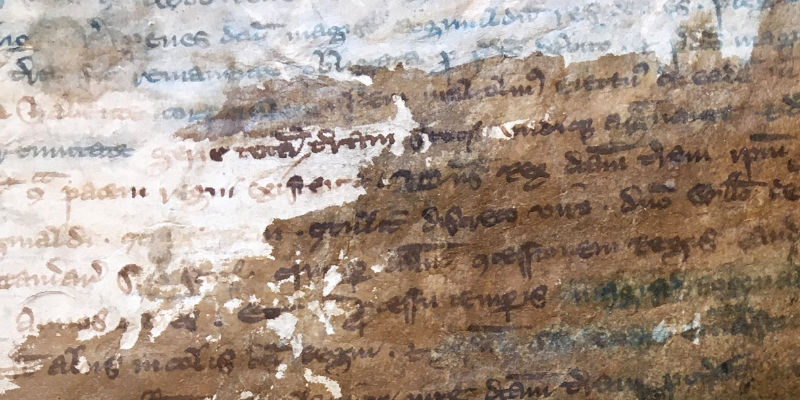

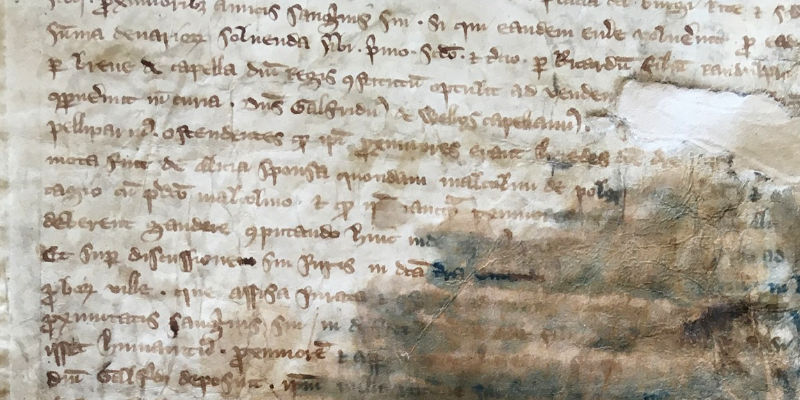

Aberdeen Burgh Court Roll of 1317

The document displayed here is the single surviving roll from the medieval burgh courts of Aberdeen, and dates from the period August-October 1317 – read more about the manuscript below.

Please click the thumbnails to view the full images.

The document displayed here is the single surviving roll from the medieval burgh courts of Aberdeen, and dates from the period August-October 1317. It is currently held by Aberdeen City Archives, reference ACA/5/6. The Stair Society reproduces images of the roll here by kind permission of Aberdeen Archives, Gallery and Museums.

The roll represents a chance (and virtually unique) survival from the courts of a Scottish burgh dating from the early-fourteenth century. Indeed, leaving aside the rolls of parliaments dating from the reign of John Balliol, it seems to be the oldest surviving roll produced by a court in Scotland to document its proceedings. To be clear, there are many records of disputes before Scottish courts dating from an earlier period than this. However, these have survived mainly in the papers of religious houses, cathedrals or noble families, rather than as part of a series of records kept by the courts themselves.

Transcription and English translation

A description of the roll and its contents is available in Andrew R. C. Simpson and Jackson W. Armstrong, ‘The Roll of the Burgh Courts of Aberdeen, August-October 1317’, in Miscellany Eight, ed. by A. M. Godfrey, Stair Society 67, (Edinburgh, 2020), 57-93 (see The Roll of the Burgh Courts of Aberdeen, August–October 1317 (stairsociety.org)). The article incorporates the transcription of the roll produced by Dr Margaret Moore in Early Records of the Burgh of Aberdeen 1317, 1398-1407, ed. by W. Croft Dickinson, Scottish History Society 49, (Edinburgh, 1957), at 1–17. In addition, it provides a translation of Dr Moore’s transcription from Latin into English.

What does the roll describe?

The 1317 roll documents the suits and actions brought before various burgh courts between August and October that year. It does not record all business that came before the courts in this period. For example, it does not record elections of office bearers within the burgh, even though this would almost certainly have happened in the October head court, which is mentioned in the text. However, when read alongside near-contemporary texts – such as the Ayr Miscellany, published in The Laws of Medieval Scotland, ed. by Alice Taylor, Stair Society 66, (Edinburgh, 2019), 445–81 – it provides a fascinating, if fleeting, insight into the practice of the law in Scottish burgh courts during the early fourteenth century. It also provides evidence of how the idea of a common set of ‘leges burgorum Scocie’ emerged, an idea also attested in the Leges Quatuor Burgorum, also known in some manuscripts as the Leges Burgorum Scocie.

Further reading

For further discussion of the roll and its context, see Andrew R. C. Simpson, ‘Urban Legal Procedure in Fourteenth Century Scotland: A fresh look at the 1317 court roll of Aberdeen’, in Comparative Perspectives in Scottish and Norwegian Legal History, Trade and Seafaring, ed. by Andrew Simpson and Jørn Øyrehagen Sunde (Edinburgh, 2023), 181–208. On the burgh laws more generally, see, for example, Hector L.MacQueen, Law and Legal Consciousness in Medieval Scotland (Leiden, 2023), ch. 4; Hector L. MacQueen and William J. Windram, ‘Laws and Courts in the Burghs’, in The Scottish Medieval Town, ed. by Michael Lynch, Michael Spearman and Geoffrey Stell, (Edinburgh, 1988), 208–27; Joanna Kopaczyk, The Legal Language of the Scottish Burghs. Standardisation and Lexical Bundles, 1380-1560 (Oxford, 2013); and Andrew R. C. Simpson, ‘Decretum fuit per burgenses: a fresh perspective on law-making in the medieval Scottish burghs’, The Innes Review, 74(1), (2023), 1–56.

Acknowledgements

The production of the images was funded by the School of Law at the University of Edinburgh and by The School of Divinity, History, Philosophy & Art History at the University of Aberdeen. Phil Astley of Aberdeen Archives, Gallery and Museums supervised the production of the images. This support, together with the permission of Aberdeen Archives, Gallery and Museums to reproduce the images online, is gratefully acknowledged. The production of the images online is an outcome in support of the Law in the Aberdeen Council Registers project, Leverhulme Trust RPG-2015-454, and with the Finance, Law and the Language of Governmental Practice project, AHRC AH/T012854/1 (for more on both see aberdeenregisters.org).